Jun

VirtuaVerse – Review

In VirtuaVerse, we explore a cyberpunk world of digital graffiti and retro hardware. Will it be lost like tears in rain? Here’s what we think.

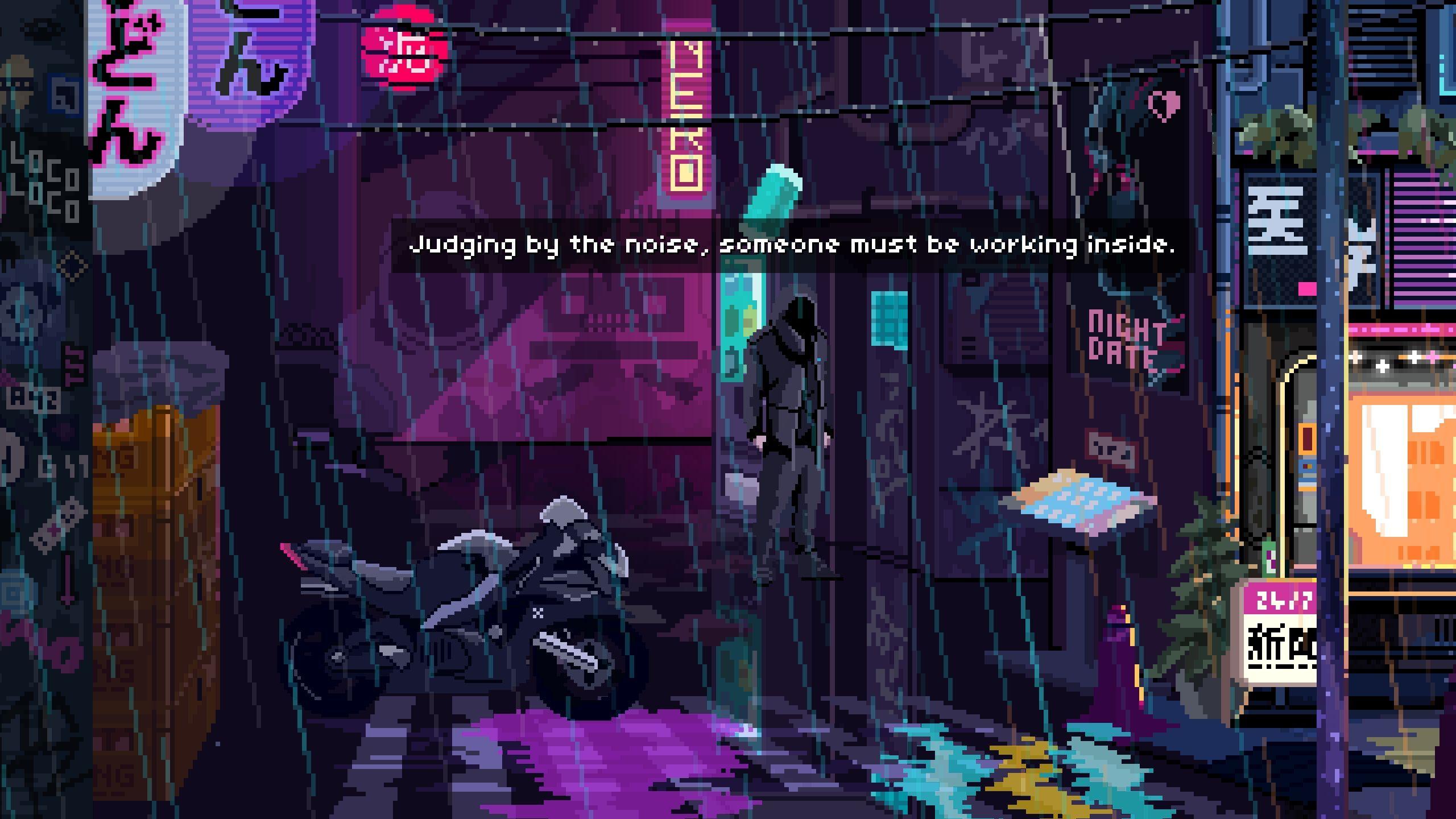

If VirtuaVerse was a rocket, then passion for the classic cyberpunk aesthetic would be its rocket fuel. You strap yourself in, and the minute you start a new game, you enter a world of gloomy nights, neon signs in Japanese, hackers in hoodies, implant-equipped cyborgs, all-powerful artificial intelligences, and cults of techno-mysticism. It’s almost a comfortable realm now. We’ve seen this specific version of the future so many times since the 1980s, after all. VirtuaVerse, in paying homage to this rather old future, ends up constructing a world that seems as much beholden to its aesthetic as to its topics. The two don’t always get along.

Our protagonist Nathan hacks hardware and cracks software for a living, and he makes it a point to live off the grid in a world where everyone is always connected to a shared augmented reality. This laid-back rebel-without-a-cause wakes up to find his punk girlfriend is missing and has left behind a cryptic message. The first act of the game strategically introduces us to the concepts of the world—AVR headsets that display a world of intrusive advertising and imagery, virtual reality experiences that have become a biological addiction, hacker groups that leave digital graffiti on slum walls, drone racers, android bartenders, and so on—VirtuaVerse populates its world with plenty of imagination.

The thrust of the conflict is that the powers-that-be have outlawed old hardware in their push for cloud integration. Between its digs at present-day cloud infrastructure and its reverence of cracker NFO messages, VirtuaVerse would seem to be making a statement in favour of an older Internet, one that the creators may be nostalgic towards. It’s that Internet where you didn’t need to plaster your real name online, and where your data belonged to you—not to a corporation server somewhere across the globe. Digs are about as far as it goes, though. Right after presenting these very current concerns, VirtuaVerse then throws at you public computer terminals and resurrects the very 20th century imagination that people will stand in a street using a terminal to read the news or chat on a dating platform. At the same time, smartphones do exist in this world, but they’re outdated technology. This begs the question—what were they replaced by?

For a game that stresses how AVR and corporate integration has taken over day-to-day life, it does nothing to illustrate this. Other than using his AVR headset to read augmented reality messages and graffiti, Nathan doesn’t require much modern tech. On the contrary, you’ll find him adding spice juice to sushi, making a makeshift torch out of wet panties, and in general, being a thorough asshole to the people around him. See, Nathan is quite alright when he’s talking. A little judgemental at times, but that adds character. The problem is that when he encounters problems, he becomes a remorseless monster. Early in the game, you need to acquire AVR glasses from a dumpster monopolised by a beggar. Nathan’s solution is to feed the beggar’s VR addiction to distract him, and the set of convoluted puzzles to do that also involves blackmailing a married shopkeeper who browses dating sites on the job. At another time, the way forward involves Nathan locking a man in his office and then refusing to unlock the door while sheepishly admitting he’s made enough of a mess already. At yet another time, Nathan takes advantage of a gang war to get a gang recruit be mistaken for the wrong gang and therefore, shot in the streets.

Nathan feels no conscience, and he gets no comeuppance. Even before his victim’s body is cold, Nathan loots the dead man and carries on his fiercely cold-hearted quest to find his girlfriend. This sheer lack of conscience becomes all the more baffling in the second half of the game, where he transforms, within seconds, from a laid-back hacker to a hero out to save the world. Why does Nathan care about people now? VirtuaVerse became difficult to tread through by the midpoint, both because of its unlikeable protagonist and its creative puzzles.

The game is a thorough homage to classic LucasArts point-and-click adventure games. That’s fine, of course. Adventure games are famously not dead now, thanks to indies. VirtuaVerse almost makes me wish they were. VirtuaVerse straddles gritty cyberpunk imagery with what is plainly silly and unintuitive puzzle-solving that adds little to the game’s narrative or atmosphere. It doesn’t even add to the game’s tone. Of course you have to hack a virtual sex booth to display a character from an old sci-fi series, so that the nightclub technician will leave his console, letting you shut down the sham concert, thereby distracting the guard, and finally letting you past a door. Of course getting to use a computer in an internet cafe involves forcing a garage mechanic to be subscribed to intrusive advertising for a whole year so that he’ll go talk to his lawyer in his office, allowing you to lock him in, damage his roof, and set loose his dog. This way, the dog will chase a cat into the internet cafe, spooking the person using the only free computer there. It makes perfect sense.

The game shirks on giving you any hints for these puzzles, forcing you to make your own leaps of logic or, well, spam inventory items on usable objects. One section with riddles is so particularly obtuse that even the game calls itself out. Given that I wanted to quit the game more often than I wanted to keep on playing it, it’s hard to recommend VirtuaVerse to anyone but the most passionate admirers of cyberpunk and classic point-and-click adventure games. Perhaps, as a game about rebels who live in off-the-grid niches, it also appeals to a niche audience.

As for me, I found VirtuaVerse more trouble than it’s worth. It’s stylish, it’s attractive, and it’s got a thumping synth-metal soundtrack (that can be a little distracting at times), but I wish I only knew it for those things, and not the ridiculous puzzles and dissonant tone.

Developer: Theta Division

Country of Origin: International

Publisher: Blood Music

Release Date: 12th May 2020 (PC, Mac, Linux)

This review is based on a copy of the game provided by the developer. The PC version of the game was played for this review of VirtuaVerse.

Thank you for reading this review of VirtuaVerse! For other interesting articles on Into Indie Games, check out the links below:

- Into Indie Games Homepage

- Indie Dev Interview: Alan Abbadessa from Little Ghost

- Are we living in a video game?

- The Signifier Walkthrough

- Wandersong – Review

- Review: TONOR TC-777 USB Condenser Microphone

WHAT DID Into Indie Games THINK?

-

TWO OUT OF FIVE STARS

Summary

VirtuaVerse’s stylish and atmospheric presentation isn’t enough to save a game constricted by convoluted puzzles and an unlikeable protagonist.